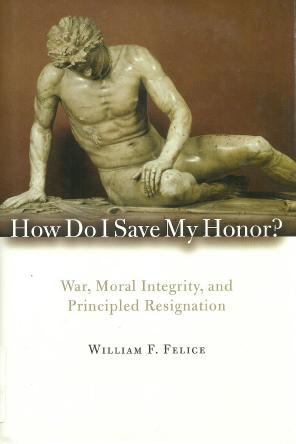

This review was posted in March, 2011. Review of How Do I Save My Honor? War, Moral Integrity, and Principled Resignation, by William F. Felice. Rowman & Littlefield, 2009, 223 pp. Reviewed by Mary Meehan What should you do if you are in the U.S. Foreign Service and are expected to support a war that you believe to be unjust? Suppose that you are the Secretary of State, faced with the same dilemma? And what if you are a U.S. soldier ordered to fight in such a war? William Felice, a political science professor at Florida's Eckerd College, takes on all of these tough questions in the context of the U.S. war in Iraq. He makes the case for "principled resignation" when internal efforts to prevent a war have little chance of success or have already failed. An opponent of the Iraq War, Felice spoke at an antiwar rally shortly before the war started. On his office answering machine after the rally, he heard an angry man say, "I think you are a traitor. I want to be the first person to put a rope around your neck and hang you in the middle of St. Petersburg [Florida] for what you told those kids down there." That was a scary experience, but one that undoubtedly helped Felice understand the worries and fears of other dissenters, including ones within the government. Probably more common than fear of violence is the fear of standing alone, especially when you're in a meeting with a President of the United States who is already committed to a war. Bob Woodward, in his book Obama's Wars (Simon & Schuster, 2010), described a dramatic moment during a high-level White House meeting on Afghanistan in 2009. President Obama asked, "Is there anybody who thinks we ought to leave Afghanistan?" According to Woodward, "Everyone in the room was quiet. They looked at him. No one said anything." So the President said, "Okay, now that we've dispensed with that, let's get on." I suspect that at least one or two people in that meeting wanted to speak up, but didn't have the courage to do so. If that's the case, they may regret it for the rest of their lives. Felice notes that General Harold Johnson, army Chief of Staff during the Vietnam War, was extremely upset when he felt President Lyndon Johnson was misleading the American people about his plans for escalation in Vietnam. The four-star general decided to confront the president, and was ready to resign, but changed his mind at the last minute. Later he told a colleague, "I should have gone to see the president. I should have taken off my stars. I should have resigned. It was the worst, the most immoral decision I've ever made." Felice interviewed a number of people, in both the U.S. and Britain, who resigned government positions because they couldn't in conscience support the Iraq War. Besides believing that the war was unjust, most of them thought government leaders were dishonest in the case they presented for the war. Their comments--and much helpful analysis by the author--are really the heart of this book. Felice sought, unsuccessfully, an interview with former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell. Many people believe that Powell, who had serious reservations about the war, should have resigned rather than become a public war advocate. Felice thinks so, too. He also believes that Powell should have expressed to President George W. Bush his concerns about war plans much earlier and more forcefully than he did. In a letter declining Felice's interview request, Powell suggested that his differences with others in the Bush administration were policy disputes rather than ethical ones. Yet ethical questions--life or death ones--are so wrapped up in war-policy disputes that no government leader has a right to overlook the ethics part. Felice believes that sometimes government officials should stay in their positions and try to change policy from within. He warns, though, that self-deception can be a problem, since it "is too easy to convince oneself that one is doing good when, in reality, by staying in the government or military one is contributing to the wrong and immoral war policy." Wayne White, he says, is one who was right to stay inside and work for policy change. He was a high official in the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) and an expert on Iraq. He was not expected to promote the war with the public--or deal with the public at all. Rather, his job was to provide first-rate intelligence and analysis to Powell and other high officials. He did that; but most of them, unfortunately, either didn't listen or didn't have the courage to act on the solid information he provided. White's fierce debates with other government intelligence officers--some of whom were all too willing to tell their superiors what they wanted to hear--led to stress-related illness for him. He remarked that "there was a price to be paid for fighting back." He also said many within government who fought for accurate intelligence were passed over for top promotions. "People who grant such promotions," he said, "want people they know will look the other way on certain occasions."  John Brady Kiesling was the first U.S. diplomat to resign over the Iraq War, taking that step a few weeks before the war actually started. "I had become more and more miserable as my nation rushed toward an unjust war," he said later. Since Kiesling had been in the Foreign Service for about 20 years, and since a friend leaked his resignation letter to the New York Times, his departure received a fair amount of publicity. Felice says that "he inspired others, in and out of government, to speak out and oppose the occupation of Iraq." Kiesling's resignation ended his depression, but also ended his career and led to serious financial problems. He paid a high price for his liberation from an impossible situation, but he has used his freedom well by continuing to analyze and criticize U.S. foreign policy. One of his most interesting comments: "The contradiction between morality and realism in foreign policy is spurious. If it's immoral, it's unrealistic. The real contradiction in foreign policy is between realism and fantasy." Felice writes about John H. Brown and Ann Wright, two other Foreign Service officers who resigned over the war. Both had interesting stories and valuable things to say about foreign policy. Brown, for example, explained how a U.S. diplomat becomes "a creature of the organization" (the State Department). But if someone becomes totally that, he warned, "then you are basically useless. You might as well be a fax machine or an e-mail system." Felice also interviewed Ehren Watada, an army lieutenant who believed the war to be illegal and immoral. Watada was court-martialed because he refused to serve in Iraq. (There was a mistrial and, after this book was written, charges against Watada were dismissed.) Another interviewee was Aidan Delgado, an army reservist who did serve in Iraq despite growing questions about that war and war in general. He sought, and eventually received, an honorable discharge as a conscientious objector. Both men were very articulate about their decisions. The Americans described in this book have not faded away, nor let their dissent be a one-time event. How Do I Save My Honor?, plus some Internet checking, showed an impressive amount of public speaking and book-writing. John Brady Kiesling wrote Diplomacy Lessons: Realism for an Unloved Superpower (2006). Aidan Delgado penned The Sutras of Abu Ghraib: Notes from a Conscientious Objector (2007). Ann Wright and co-author Susan Dixon produced Dissent: Voices of Conscience (2008). Wright helped Cindy Sheehan run Camp Casey, the antiwar protest site near then-President George W. Bush's Texas ranch. Wright also was arrested a number of times for civil disobedience against the war. Delgado, too, became an ardent antiwar activist. Felice's chapter on resignations of principle in Britain is interesting and valuable. It would have helped, though, to have information on the difference between cabinet members and cabinet ministers and an explanation of "parliamentary private secretaries." The terms are confusing to people from non-parliamentary nations. Deeply divided over the Iraq War, Britain had far more resignations by government officials than the United States had. Felice says the British have a stronger tradition than Americans do about resignation on principle. I believe this is true. But it's also my understanding that British government officials who cannot publicly defend a key government policy are expected to resign, even if that policy is not in their specific domain. Most cabinet members, and some "junior ministers" who serve under them, are also Members of Parliament (MPs). They are supposed to be knowledgeable and outspoken on many issues; but the party in power does not want its cabinet members to be fighting with one another in parliament. By contrast, U.S. cabinet members who head domestic departments such as education or transportation might be tolerated if they privately disagree with a decision to go to war but do not make an issue of it. Since they don't serve in Congress, and thus don't have to debate or vote on policies outside their domain, they might simply be quiet about the issue. The British system also makes resignations financially easier for many officials than it is in the U.S. British politicians can resign cabinet or sub-cabinet positions without resigning from parliament, and that's what most of the Iraq War dissenters did. So they still had financial security and were still in politics. This is not to say, though, that British resignations of principle are necessarily penalty-free. Felice reports that Clare Short, a cabinet member who resigned over the Iraq War, thereby "cut her salary in half, reduced her pension, and debilitated her future political prospects." Short caught criticism from antiwar forces because she didn't resign just before the war started, as others did. But she did resign two months later, saying that Prime Minister Tony Blair had broken promises he had made to her about United Nations involvement in the occupation and reconstruction of Iraq. Then she was more or less ostracized by Blair's Labour Party despite her long commitment to it. "If you are an older MP and want to go to the House of Lords," she told Felice, "you'd better keep your nose clean. If you are a younger MP and you ever want to be a minister, you better not rock the boat. And the party leadership is quite ruthless." Carne Ross, a veteran of the British Foreign Service, also suffered when he resigned in 2004. He gave up his salary and career and apparently took a major cut in his pension. He had considered resigning before the war started, but didn't because "I was afraid of being publicly humiliated." During the run-up to the war, he was a British diplomat at the United Nations in New York, where emotions about 9/11 were still high. "To stand up in front of that runaway train carried a risk you would have been crushed," he said, "and I wasn't prepared to endure that." But he was later called to appear before an official British panel on the Iraq War, and "I wrote down all that I thought about the war, including the available alternatives, its illegality and the misrepresentation of what we knew of Iraq's weapons. Once I had written it, I realized at last, after years of agonizing, that I could no longer continue to work for the government." Looking back on his Foreign Service work, Ross commented: "In government you are implicitly taught in various ways that governments sometimes have to do dirty work in order to protect their peoples, to protect their interests. There is a certain amorality which is acknowledged in government, sometimes even celebrated.... The business of state craft is seen as such an amoral practice, that even to talk about morality in that context is viewed as naïve. I mean, you would not be having this conversation inside the foreign office. Talking about morals is not really encouraged." He added: "It is a hard-headed business where you are supposed to look at the world through cruel, cold eyes and disinterestedly, dispassionately assess what your country wants and then go out and get it." This is something that idealistic young people should ponder if they are considering a career in the diplomatic service or the military. Ann Wright, who had long experience in both, noted that some people in government "will not work on programs that they disagree with. They ask for a transfer or a change..." That is one way to send a message; but the request may not always be granted, especially in wartime. It seems to me that those entering government service should go in with the understanding that they may have to resign on a matter of conscience at some point. They will find such decisions less painful if they have modest lifestyles, stay debt-free, and build up their savings quickly. If they do this, resignations need not mean financial catastrophe for themselves and their families. Others, already in government service and worried about things they are asked to do, can profit by the experience of people described in this fine book. When I obtained How Do I Save My Honor? through inter-library loan, I was pleased to see that it came from the Nimitz Library at the U.S. Naval Academy. I thought it an excellent book for officer trainees to read and discuss in class. Later, though, I noticed that the "Date Due" slip in the back had just one entry: Nov. 24, 2009. C'mon, guys, you can do better than that! Our elected officials, also, should read Prof. Felice's book. If more of them acted with honor and courage, it would be much easier for appointed officials and soldiers to do the same. Right now, decision-making at the top is so poor that many diplomats and soldiers find it very hard to keep their honor while they serve the country they love.  |